In my previous post, I briefly wrote about what I called the English Round Hand’s “sub-styles”. Today I want to take the time to explain what I meant and show you what those styles are.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, professional scribes had to learn a wide variety of hands because different styles were associated with different functions. They had to use one specific style for business documents, another for private correspondence and a third one for legal documents ; plus every country had their own national hands, which weren’t always legible for the foreign eyes…

In many European countries, the 50 or so different styles commonly used in the beginning of the 17th century made the ability to write a rare skill that only the best writing masters could achieve. However, as more and more people needed to be able to write to conduct their businesses in the modern world, writing had to become less exclusive and only the simplest hands could survive.

At the time, the big European Countries were competing to grow their areas of influence. After the French parliament limited the number of official writing styles to only three, in 1633, the French Batarde (the French trade hand) became very popular in other European countries, including Great Britain, contributing to placing France at the center of attention when it came to trade.

But by the end of the century, the British Empire was growing its own influence, and Writing Masters in London decided that using a foreign hand was no longer acceptable : they had to develop a truly national hand, a standardized style easier to read and faster to write ; a hand that would be used for business, perfectly fit to promote the image of a growing commercial empire.

It is in this context that the English Round Hands were developed in the first half of the 18th century. I’m insisting on the plural here, because many copybooks do mention the existence of multiple “round hands”.

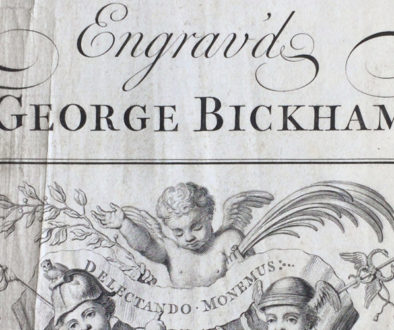

In 1741, George Bickham included a table of the styles he used at the end of his Universal Penman. Three of the hands illustrated there look very similar :

It turns out that because writing was so codified, the style that we now identify as the English Round Hand or Copperplate script was actually a family of similar hands of different sizes and formality, each one used for a specific purpose.

There were 2 formal styles :

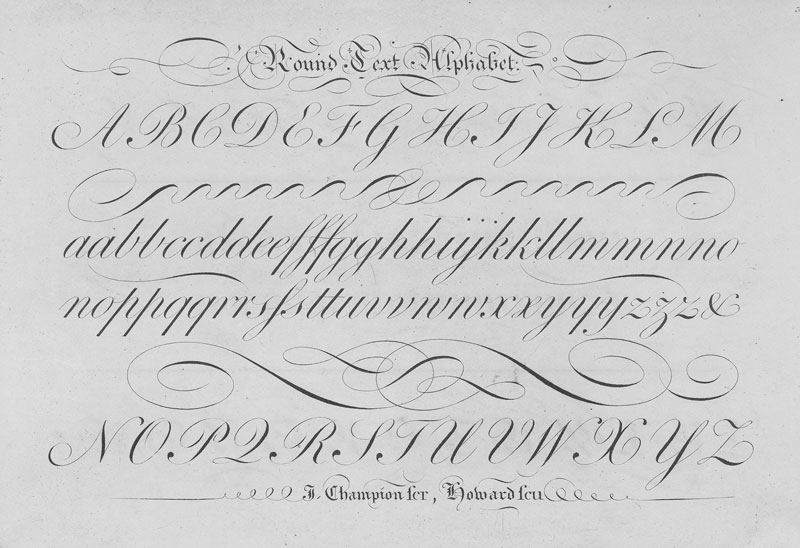

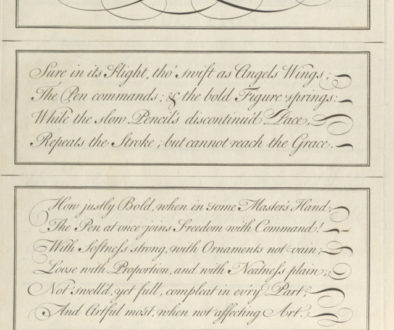

- The Round Text Hand would be used to write titles and subtitles. Here, “Text” means “large, formal”, which makes it suitable for important business documents. This hand is a bigger version of the Round Hand with a more formal look, no loops and often ornate capital letters with extravagant flourishes. Contrary to what is sometimes said, it is not a handwriting style as the letters are carefully and consciously drawn. As for all the other hands, a broad cut quill was used to write Round Text… but as the hand was written bigger, the pen was broader.

Round text exemplar, from J. Champion, New and Compleat Alphabets, 1754

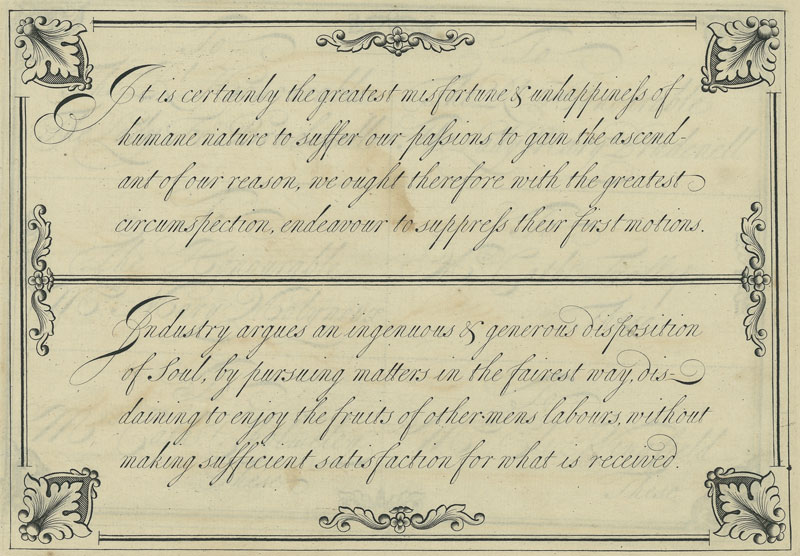

- The Round Hand was the smaller version of the Round text, it was used to write longer bodies of text on business documents like invoices, bills of lading, etc. This middle-size script has some loops on ascenders and descenders, capitals are often simpler, so they can be executed in one swift movement. The flourishes are not over the top, mostly kept at the beginning and end of a line. The style is extremely easy to read, but it doesn’t really allow for fast writing either.

1 Handwriting style (handwriting is internalized and spontaneous, it is meant to be written faster)

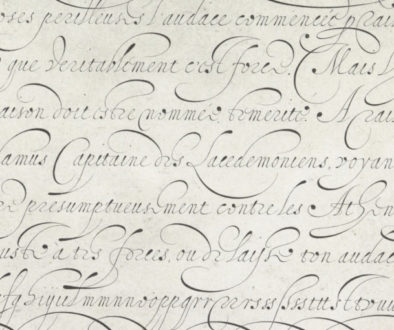

- The Running Hand is the most cursive of the family, the fastest to write and the one an Englishman would use for correspondence. This is a nice flowing handwriting style, characterized by its proportions that allow long and loopy ascenders and descenders and bigger capitals. In business correspondence, a larger and occasionally more decorated style was used for the initial “Sir”. If the writer was confident, he would also execute some decorative flourishes in strategic places. This style definitely emphasises movement and spontaneity. Along with the Italian hand, this style was written using an almost pointed, flexible pen.

1 Ornamental style

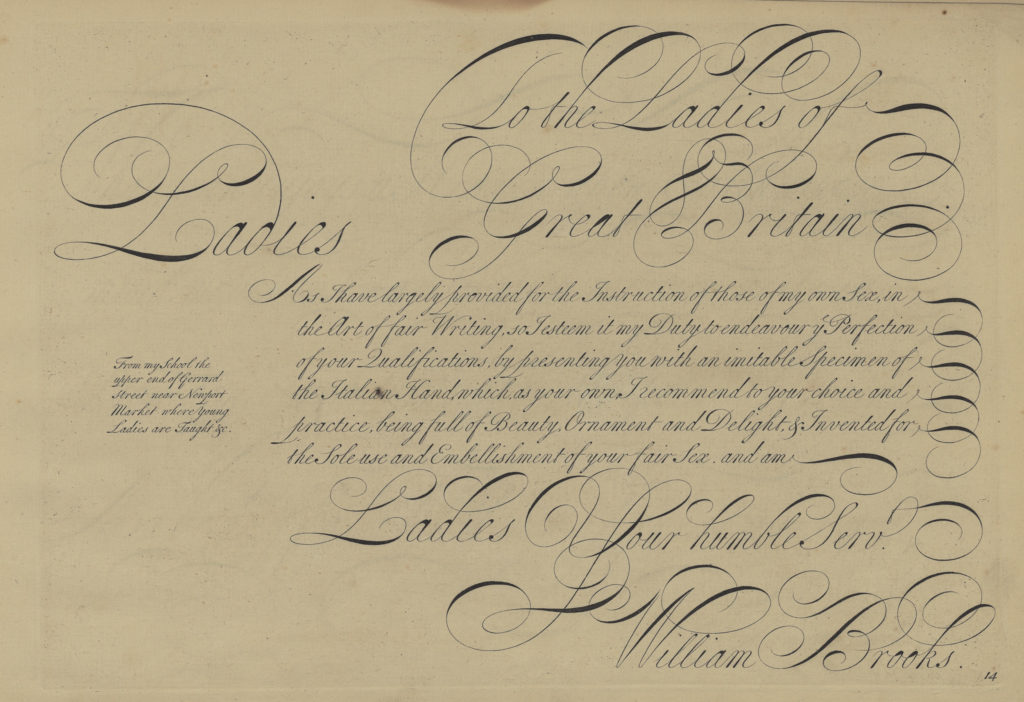

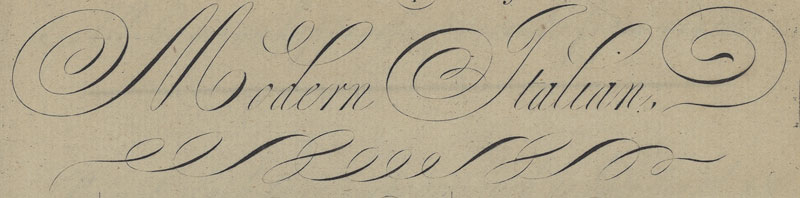

- The Italian Hand shown in the Universal Penman was inherited from the cancellaresca corsiva developed in the late 16th century in Italy. It is narrower and more slanted than the English Round Hands (around 52°), and is written with less contrast of thick and thin strokes. This lack of contrast made it easier to learn and therefore ideally suited as a handwriting style, particularly recommended for ladies1I’ll tell you more about this hand in a future post ;) .

But 18th century Writing-Masters used it mainly for ornamental purposes in their copybooks : to write flourished headlines and titles. This formal version was written with a different penhold that makes it appear as if it was written backwards, and it was sometimes referred to as Italian Text.

J. Champion, Penmanship Exemplified, 1758

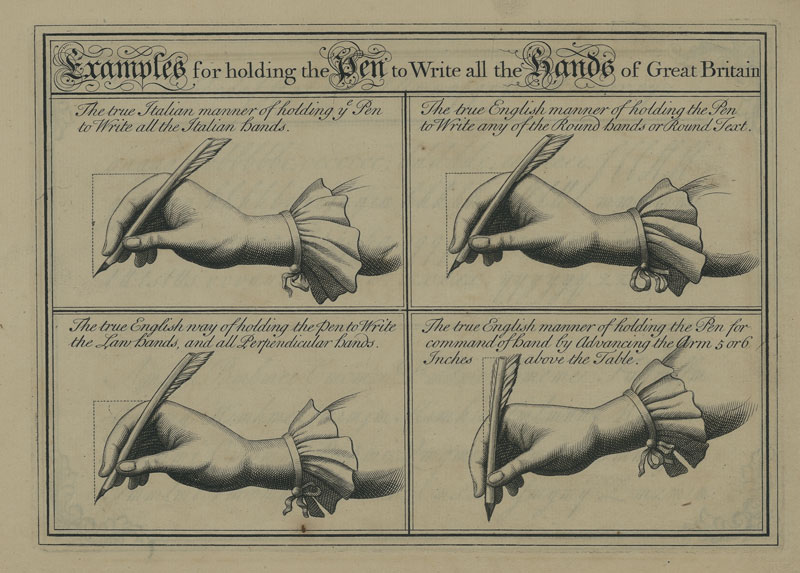

All of these hands were taught separately, they featured different sets of letter variations and were written using different tools…

The new Round Hands quickly became the prominent style in the Empire, but the older hands did not completely vanish. Indeed, in 1770, Joseph Champion’s son explained that of the 17 hands still taught in Great Britain, only 4 were useful for trade (these are the Round hands) and 3 for the practice of the law – but using these hands was mandatory2Joseph Champion Jr, Penmanship or the art of fair writing, p.5, 1771 ; the remaining styles were only used for ornamental work – in other words for “Calligraphy”.

Today, we use the same nib regardless of the size we write at and all of the Round hand styles have merged into one big confusing style. But I think it’s interesting to learn to recognize each of these styles in old copybooks : by studying each of them separately, we can learn a lot about what makes a script consistent in its elegance or (apparent) simplicity. For me, it also makes the study of copybooks a bit less confusing… Tell me what you think ;)

interesting. I see a form of the Langdon New Copy Book from 1723 still in use in the 1870’s in the US. I have sort of collected common hand-written documents from the 19th-century to study regular penmanship. (more like penmanship as used, rather than penmanship as taught) I have some letters from the 1870’s from a railroad company’s office and one of the documents looks very like this style of writing. Interesting how some styles last long after they’ve fallen out of fashion, or continue to be taught in out-of-the-way places long after they’re no longer in fashion in the… Read more »

The Italian hand is the older than the RH, it was very popular before the RH took over and stayed in use probably because it was so popular… It was recommended for ladies in particular, and I’ve seen it in American copybooks after 1850. Was the document you have seen written by a man ? When you look at the examples I posted, the main difference (aside from shade placement) between running hand and Italian is the fact that the Italian has more curves where the running hand has straight lines… Look at the second part of the n or… Read more »

I’m very anxious to learn the reason why you mentioned that The Italian Hand is” particularly recommended for ladies “. Should you explain it? Thanks a lot.

Hi,

Yes ! The Italian hand was recommended for ladies mainly because it looks more graceful than the more sturdy round hand… Back then, they believed that men had to write a certain way (have a handwriting that reflected male qualities, and legibility was not recommended for some reason), and women had to use a hand that reflected female qualities : gracefuness, lightness of hand, subtelty, legibility… To my knowledge, the only men that used Italian hand were Writing masters… but I can be wrong.