16th century : the rise of the writing master

The invention of printing in the middle of the 15th century had a dramatic impact on the way books were produced and consumed, and – by association – on the role that scribes played in society. While printing quickly became the prevalent method by which books were produced, the documents used in business, legal and financial transactions continued to be handwritten… As the medieval scribe disappeared, the economic and social context of the Renaissance – starting in Italy – allowed teachers of handwriting (writing masters) to massively emerge, and the invention of printing allowed those men to publish manuals that would help students in the practice of writing.

These “copy-books” not only served as models to copy from, but also served to publicize the work of the masters and guarantee their reputations well beyond the frontiers of their respective cities and countries. Italy was the precursor in this field (as in many others), the cancellareca (italic / chancery hand) and the more cursive “italian hand” quickly seduced scribes… Arrighi, Tagliente, Palatino and Cresci’s books influenced the development of handwriting all over western Europe, and their success inspired many writing masters up until the 20th century.

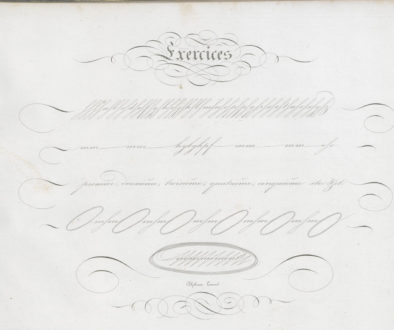

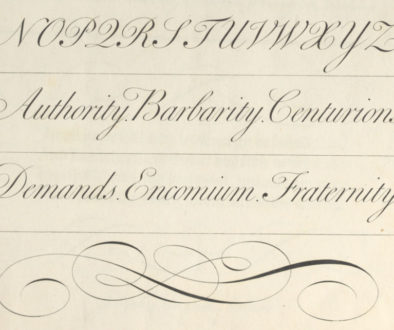

The first writing copy-books were all printed from woodcut plates. The method gave acceptable results, but writing masters knew that they couldn’t rely on the engraver to reproduce finer details. Their designs had to stay relatively simple, and their copy-books only conveyed the basic principles of the various writing styles represented.

However, engravers were finally able to reproduce good letterforms on copper-plates around 1570, and the copy-books themselves began to change. The results were stunning : the subtle contrasts of the printed letterforms were enhanced by the new method of engraving, it gave a crisper image and allowed to reproduce small examples of the script as well as elaborate flourishings known as ‘command of hand’. From then on, writing-masters wouldn’t have to just focus on giving basic instructions on writing in their books, they would be able to design and publish the most elaborate artworks… as long as a good letter engraver was around.

Italy

ARRIGHI (Ludivico Vincentino, degli), La Operina, 1522.

The first writing manual on Cancellaresca (Italic script). Arrighi was a writer of briefs in the Papal Chancery where the new cursive hand had been developed, he turned to printing (and teaching) after losing his job. If you’d like to see some of his original work, the Spanish National Library digitized a manuscript of Petrarch’s works by the hand of the Italian master.

TAGLIENTE (Giovanni Antonio), Lo presente libro insegna la vera arte de lo excellente scriuere…, 1524.

Tagliente was a teacher of handwriting in the Venetian chancery, his book was published shortly after Arrighi’s La Operina, and was his most influential manual (at least 30 editions were published in that century alone !). The plates display a less stilted style of chancery, but bear in mind that not everything was handwritten : some of the pages were printed from types cut to resemble his script.

PALATINO (Giovanbattista), Libro nuovo d’imprare a scrivere tutte sorte lettere antiche et moderne, 1540.

With this book, Palatino intended to appeal to a wider audience than his predecessors (Arrighi and Tagliente) : his plates not only show his own version of the chancery but also include samples of many other hands in use in Italy at the time. The second part of the book deals with cryptography and the third demonstrates unusual alphabets. The link will take you to a later edition of the book titled Compendio del Gran Volume de l’arte bene et liggidramente scrivere (1566).

AMPHIAREO DA FERRARA (Vespasiano ), Opera di frate Vespasiano Amphiareo da Ferrara dell’ordine minore conventvale, nella qvale s’insegna a scrivere varie sorti di lettere, 1572.

According to Joyce Irene Whalley, Amphiareo’s work is important in the development of the chancery cursive script : his use of loops and joins more common in mercantile scripts helped to produce a more speedy hand. This book was first published under the title Uno novo modo d’insegnar a scrivere in 1548.

CRESCI (Francesco), Essemplare di piu sorti lettere, 1560.

Cresci introduced a different type of Cancellaresca after criticizing the models of Palatino for being too slow to perform. His own models proposed a speedier, more practical hand for correspondence and book-keeping. One of the most visible changes to the chancery italic was the introduction of “clubbed” ascenders, made with a looped circular movement that produced a blobbed top. This book is where the “Italian hand” practiced today finds its roots. Cresci’s work was extremely influential and shaped the evolution of handwriting in Europe until the beginning of the 20th century.

ALDROVANI (Ulisse), Manuscript in italian hand, c.1560-1600 ? (added september 2020)

A beautiful manuscript written in an italian hand style close to Cresci’s. These handwritten pages are a beautiful example of the use of the hand “in real life”, the imperfections and variations of slant and form give life to the hand.

HERCOLANI (Giulantonio), Lo Scritor’ Utile, 1574.

Hercolani’s works were among the first to be printed from copperplate engravings. This book is Hercolani’s second publication. Comparing the plates with the copybooks mentioned above, you will be able to get a better idea of the freedom conferred on the scribe by this new method of reproduction.

SCALZINI (Marcello), Il Secretario…, 1587.

Most of the book deals with the Cancellaresca Corsiva developed in the Papal chancery, with a special emphasis on the need for speed. It also displays some examples of big flourished decorations, made possible by the new printing technique.

CURIONE (Ludovico), La notomia delle cancellaresche corsiue, & altre maniere di lettere, 1588.

Most of the plates are devoted to the chancery hand, including “lettera corsiva” variant, and “Lettre que escriuent les dames de France”.

SCIPIONE (Leone), Examples of the Chancery hand, 1598.

Typical examples of the “Italian hand” in the style of Cresci.

Spain

ICIAR (Juan, de), Recopilacion subtilissima : intutilada Orthographia practica…, 1548.

Iciar (or Yciar) likely spent some time in Italy before writing this book : he drew inspiration from Palatino’s work and may have studied with him. The plates in this book were beautifully engraved but Iciar’s work had little influence in Spain and was eclipsed by Francisco Lucas’s publications (circa 1580).

ICIAR (Juan, de), Arte subtilissima, por la qual se enseña a escreuir perfectamente…, 1553.

This is a second, enlarged edition of Iciar’s previous title. Both books contain some remarkable examples of white on black printing, with beautiful ornaments and illustration.

LUCAS (Francisco), Arte de escrivir…, 1571.

The link will take you to a reprint from 1608, which seems to be the last reprint. Lucas’ work was specially significant in the development of two major Spanish hands : the Bastarda and the Redondilla, which remained in use in Spain for several centuries. The Redondilla was a combination of the italian chancery and local mercantile hands while the Bastarda was a cursive version of the Redondilla.

France

HAMON (Pierre), Recueil d’alphabets et d’exemples d’écritures anciennes, 1566.

(Manuscript)

HAMON (Pierre), Alphabet de Plusieurs sortes de lettres, 1567.

Pierre Hamon attempted to collect as many old and contemporary writing models as possible in this book. Some styles are very odd and not very practical… It has been recently established that this is the first known copybook to have been printed from copperplates.

DE LA RUE (Jacques), Exemplaires de plusieurs sortes de lettres, 1569. & Alphabet de dissemblables sortes de lettres italiques…, 1565

Both books are bound in one volume. They provide examples of the different hands used in France at the time, including the French gothic handwriting (now called “lettre de civilité”) and some examples of “Italics” and “Italian” hands.

BEAUCHESNE, (Jean, de), Le Tresor d’escriture, auquel est contenu tout ce qui est requis & nécessaire à tous amateurs dudict art.., 1580.

Like some other French masters, Beauchesne was a Huguenot (a French protestant) who had to exile himself for religious reasons. This is his second publication, which was influenced by his travels in Italy. His first copybook (A booke containing divers sort of hands) had been published in London in 1571 with the help of John Baildon… and is known as the very first English copybook. A nice manuscript (different works) from the same author can be found here.

BEAULIEU, Exemplaires du Sieur Beaulieu : où sont monstrées fidellement toutes sortes de lettres et caracteres de finance…, 1599.

Little is known about this master from Montpellier. Most of his book is dedicated to the French gothic hand, but a few beautiful plates show his specimens of “Italian hand”. The beautiful illustrations on the title page show the author’s erudition.

LE GANGNEUR (Guillaume), La Technographie ou brieve methode pour parvenir à la parfaite connoissance de l’ecriture françoyse ; La Rizographie ou les sources, elémens et perfecçions de l’ecriture italienne… ; La Caligraphie ou belle écriture de la lettre grecque, (Three books in one volume) 1599.

Le Gangneur was an extremely respected calligrapher, secretary to Henri III and Henri IV. These three books were beautifully engraved by Frisius (the best letter engraver of this period). The first book is dedicated to the French gothic, with a plate that shows the small letters in great detail ; the second book is dedicated to the italian hand, and the third to the greek letter. For each hand, he shows his penhold and many beautiful variations.

Low Countries

MERCATOR (Gerard), Literarum latinarum, 1540.

Mercator was a renowned geographer and the founder of cartography school in (what is now known as) Belgium. He wrote this book of instructions on how to write the chancery script with cartographers in mind. It was the first of the genre in the region and only the third manual, chronologically, to deal with italic script.

PLANTIN (Christophe), ABC, ou Exemples propres pour apprendre les enfans à escrire..., 1568.

Plantin was a very successful printer in the Southern Low Countries (Antwerp) : he published many books on different subjects and had a talent to know which publications would appeal to the public. This book was aimed at children and young people who were learning to write and provided good examples of various handwriting styles in the form of “maxims” supposed to “shape” the young person’s mind.

PERRET (Clement), Exercitatio alphabetica, 1569. (added July 2020)

Until recently, this was believed to be the first published copybook printed from engraved metal plates (intaglio), rather than from woodcuts. Clément Perret was a very young writing master from Brussels, Belgium. The book is very rare and stayed under the radar for a long time. It is possible that the Flemish engravers had gained expertise in the engraving of the chancery hand through engraving maps (map makers had been seduced by Mercator’s copybook). The engraver who worked on the book, Cornelis de Hooghe, was in fact renowned for his works in map engraving. The illustrated borders are particularly remarkable in this book.

BOISSENS (Cornelis), Promptuarium variarum scripturarum…, 1594.

Cornelis Boissens collected calligraphy and art, he left useful comments on Dutch calligraphers from his time (this is the beginning of the Golden Age of Dutch calligraphy). He was opposed to the use of superfluous ornamentation in calligraphy – even though his book does not exactly reflect that, it is an example of ‘sober’ Dutch calligraphy. Boissens engraved his own books.

HONDIUS (Jodocus), Theatrum Artis Scribendi, 1594.

This succeful book was a collection of the greatest masters of the time : the English Bales and Billingsley, the Dutch Caspar Becq and his talented assistant Jan van de Velde, Maria Strick, and the works of the three winners of the Rotterdam Golden Quill contest of 1590 (Van Sambix, Hendrix and Velde). Hondius was better known for his work as a map engraver, his calligraphy was greatly inspired by Mercator and Perret.

Germany, Switzerland…

WYSS (Urban), Libellus valde doctus elegans, & vtilis, multa et varia scribendarum literarum genera complectens, 1549. (Switzerland)

Wyss’ work had a significant influence in northern Europe during the 16th century. Some of the woodcut illustrations used here were copied in later books and copybooks. The plates provide a good overview of all the contemporary and historical hands in use at the time, with a focus on “German” styles.

FUGGER (Wolfgang), Ein nutzlich vnd wolgegrundt Formular Manncherley schöner schriefften, 1553.

Lots of explanations and examples of early Kurrents and German chancery hands, some beautiful Fraktur, Textura and Rotunda exemplars and an early flourishing systematic (for Fraktur capitals).

Fugger’s “Latin” scripts are not as well made as his Gothic hands. He was the most famous pupil of Johann Neudörffer.

NEUDORFFER (Johann), Ein gute Ordnung und kurtze unterricht der fürnemsten grunde…, 1555.

Neudörffer was the most influential writing master in Germany at his time. He was (among others) responsible for how Fraktur developed and wrote the inscriptions on Dürer’s apostle paintings. He was famous for his hands-on teaching – he already started with basic strokes and what we could call drills today, and then went on to letters. He did not use gudelines of any sort. “Ein Gute” is one of his major copybooks, but it contains no explanatory test. He published more in depth explanations in another book, Gesprechbüchlein, that was reissued by his grandson Anton, in 1601.

BOCSKAY (Georg), Mira calligraphiae monumenta, 1561. (Austria)

Bocskay was imperial secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, he created this book as a demonstration of his own pre-eminence among scribes. It is not a writing manual, and only exists as a manuscript, but it does include a wide variety of contemporary and historical scripts. Years later, Bocskay’s beautiful calligraphy was exquisitely illuminated by Joris Hoefnagel.