We have seen that in the 16th century, Italian writing masters had been at the forefront of the innovation in the world of copy-books. In each european country, scribes still used a variety of national hands designed for specific purposes : they had to use different styles based on the kind of document they were writing. With the expansion of trade relations in Europe, the demand for people with a good writing hand grew, and so did the need for a business-appropriate style that everyone would be able to read and write. The “up and coming” Italian hand (cancellaresca corsiva) was perfect for this role, so it is not surprising that as the 17th century unfolded, the place it occupied in copybooks grew as well.

However, Italian masters lost their place as the most influential people in the world of scribes. Before the turn of the century, masters in the Dutch Republic had started to produce copybooks of very high quality thanks to some extremely talented letter engravers (who often happened to also be calligraphers). Around 1600, the production of such books increased with some prolific writing masters like Jan van de Velde, Cornelis Boissens and Maria Strick, whose publications traveled accross borders and influenced scribes abroad.

But around the 1640’s it seemed that the heyday of the Dutch copybook was over and France took the lead in the publication of influential writing books. Like all of the other countries in Europe, France had had its own set of gothic handwriting styles to which the “humanistic” italian hands were added. But the French felt that having so many very different styles in use was very confusing. In 1632, Louis XIV’s minister Colbert asked the guild of the “Maitres Ecrivains” to rationalize and even regulate the art of writing. As a result, only 2 major hands were allowed to be taught in France : the Ronde – which was a mix of humanistic and gothic hands – was the principal formal hand to be used in official documents ; and the Italian (or French) Batarde which had been developed from Cresci’s cancellaresca corsiva (italian hand), popularized by Lucas Materot in 1608. A third hand, the Coulée, would come at the end of the century. From the 1630’s, French masters were allowed to only teach these 2 or 3 hands, and this was of course reflected in their numerous copybooks.

Meanwhile, in the growing British Empire, and more specifically in London, writing masters took their time to start making good looking copybooks. They had access to the beautiful books produced by the Italians, the Dutch and the French, and seem to have been quite satisfied with that for a few decades. However, penmen did publish copybooks until the market was described as “saturated” with books of questionable quality, which led more talented masters to react and publish their own – better – examples. Like in the Dutch Republic, these books included “all the hands” useful to scribes, including the Italian hand, the importance of which grew as the century passed. Like everywhere else, the main problem for the masters was to find a good engraver, many decided to do it themselves, yielding various results…

The best known English master of this century was Edward Cocker, whose extremely ornate style reflects the baroque aesthetic typically present in many copybooks of this era. However, towards the end of the century, new masters like John Ayres, who liked more sober designs influenced by the clean French hands, paved the way for a new and more rational English hand that would eventually replace the traditional styles.

Many copybooks were published in the 17th century, this list only includes those that I could find online and reflects my own interests. I’m sure that some books are missing, so please get in touch with me if you’d like me to add anything !

Dutch Republic and Southern Low Countries

VAN DEN VELDE (Jan), Manuscript, c.1598. (added : May 2020)

A manuscript from the young master, a few years after he won 3rd prize at the “Prix de la Plume Couronnée” (he was 29 at this point). Sadly, the images can’t be seen in hi-resolution, but these page give a nice view of the master’s talent before he published his first books.

VAN SAMBIX (Felix), A manuscript., circa 1600.

Felix Van Sambix was one of the most illustrious penmen in the Low Countries at the end of the 16th century. He had won first prize at the “Prix de la Plume Couronnée” in 1590, back when Velde was a youngster… I couldn’t find any of his publications online, but this manuscript his a beautiful example of his abilities as a penman.

VAN DE VELDE (Jan), Deliciae variarum, insigniumque scriptuarum, 1604.

Jan Van de Velde is undeniably the most famous of Dutch penmen, and of course an incredibly talented calligrapher. Some of his work had already been published in Hondius’ Theatrum Artis Scribendi in 1594, after he had won 3d prize in a calligraphy contest, but the young Velde had not yet reached the peak of his talent. This Book is Velde’s first of many copybooks. It is not as spectacular as his masterpiece, the Spieghel der Schrijfkonste (1605), but it already shows the immense talent of the Master. In all of Velde’s books, you will find examples of the Flemish cursive hand, of gothic cursive and formal hands, and of course italic and italian hand. As the director of a French school, he excelled in the French hands as well. Also, if you like luxurious flourishes, Velde is a master to study in detail.

BOISSENS (Cornelis), Grammato-graphices, 1605.

This is Boissens’ third publication, engraved by the master himself. It mainly includes examples of the Flemish cursive and gothic hands, and includes a few pages of italian hand.

VAN DE VELDE (Jan), Spieghel der Schijfkonste, 1605.

Velde’s most famous – and probably most beautiful – publication, engraved by the famous Simon Frisius. In the 59 plates, Velde included specimens of each of the major hands practiced in Europe at the time, and gave ample information on the various cursive hands and the best way to write them. This book is one of the most famous copybooks ever printed, many copies can be found online. The link I provided in the title will take you to the Rijksmuseum’s website, where you will be able to see the printed pages next to the original handwritten pages in hi-res, and see for yourself the very subtle difference between engraved and handwritten letterforms.

VAN DE VELDE (Jan), Exemplaer Boec inhoudende alderhande’ Gheschriften…, 1607. (Also at the British Library)

Another good example of Velde’s talent and artistic skills…

STRICK (Maria), Tooneel der loflijcke schrijfpen…, 1609.

Maria Strick, one of very few women to have published copybooks, was a very talented penwoman who rightfully won a prize for her beautiful italian hand in 1620. She was the daughter of Caspar Becq (Velde’s master). Her husband beautifully engraved her copybooks and refused to work for other writing masters.

FRISIUS or DE VRIES (Simon), Lust-hof der Schrijf-konste gheschreven…, 1610.

Frisius is better known for his work as “the best” letter engraver of his time. As such, he worked for a few French and Dutch masters. This copybook shows that he was also very talented as a calligrapher, specially when it comes to the Dutch hands, which he seems to have favored.

STRICK (Maria), Christelijke A.B.C…, 1611.

FOPSZ (Lucas) LELY, Leughts nut’lyck ABC…, 1614.

Lucas Fopsz Lely was one of the many talented Dutch writing masters of this era. This books is typical of Dutch copybooks from this period, and contains a few model of gothic hands and italian hand. The same book was bound with a copybook published by Velde in the same year (see link below).

VAN DE VELDE (Jan), Het eerste deel der Duytscher ende Franscher Scholen exemplaer-boeck, 1614.

Another one of Velde’s copybooks, bound with Lucas Fopsz’s above mentioned book.

CORNELISZ (Otto), Collection of manuscripts, 1615.

ROELANDS (David), T’Magazin…, 1616.

This book , engraved by Frisius, contains examples of many different hands and beautiful calligraphic borders. Roelands obtained the rare privilege to copyright his models in order to prevent his plates from being copied by unauthorized engravers (pirate copybooks were unfortunately quite common).

CARPENTIER (Joris/George de), Exemplaer Boeck, 1618.

George de Carpentier was Velde’s son in law. We know that he won the first place at the “prix de la Plume Couronnée” in Den Hague in 1620 and complained that Maria Strick was second with a special mention from the judges saying that her Italian script was superior… He asked the judges to choose the winner based on his / her all-round calligraphic ability rather than because they excelled in just one category of script. Apparently, Strick was boasting a bit too much about her superiority…

VAN DE VELDE (Jan), Duytsche exemplaren van alderhande gheschrifften Seernütende bequaem…, 1620.

As the title suggests : this book includes mainly Dutch styles of writing.

VAN DE VELDE (Jan), Het derde deel der Duijtscher ende Franscher Scholen Exemplaer-boeck, 1621.

This is the third volume of the series of books dedicated to the Dutch and French hands he taught in his own school. This time, it includes much loger texts like models of letters.

VAN DE VELDE (Jan), Thresor literaire contenant plusieurs diverses escritures les plus usitées es escoles Francoyses des Provinces unies du Pays-Bas, 1621.

Probably the master’s last copybook.

KLEPP (Gegorii), Theatrum Emblematicum, 1623.

I’m not sure Klepp was Dutch, but this book illustrates the Dutch style (with some borders clearly inspired by Velde). It also contains a few pages in humanistic minuscule (foundational script) and some interesting illustrations.

STRICK (Maria), Fonteyne des levens dat is schoone…, 1624.

DE SWAEF (Samuel) & LANCEL (Henry), Gedichten van verscheijde poëten…, 1628.

Two schoolmasters combined forces to put together this copybook displaying nice examples of the most useful hands, written by eight writing masters of very good reputation in the Netherlands (including De Swaef and Lancel themselves). De Swaef engraved the plates himself.

VAN [DEN] HORICK (Baldericus / Baudry / Balderic), Schreibmeisterbuch…, 1632.

Horick wrote this book (manuscript) of models for the Duke Wolfgang Wilhelm von Pfalz-Neuburg to whom he probably taught penmanship. The book contains examples of calligraphy in several languages and hands. Horick excelled at “offhand flourishing” (or Striking) and left an impressive amount of such “drawings” of animals and sometimes portraits beautifully executed.

VAN [DEN] HORICK (Baldericus / Baudry / Balderic), Livre contenant plusieurs sortes d’escritures avecq divers traicts…, 1633.

Another manuscript example of Horick’s mastery, including magnificent flourished animals and models of Dutch gothic cursive and Italian hand. Horick didn’t publish any engraved copybook and thus remained relatively anonymous, but this allows us to see some actual handwritten forms.

DE LA CHAMBRE (Jean), Exemplaer-boeck inhoudende verscheijden geschriften…, 1649.

Jean de la Chambre was also teacher in a “French school”, his work shows that he was inspired by the Dutch masters who came before him, but his style is more sober in its design.

PERLING (Ambrosius), Exemplaar Boeck inhoudende verscheijde nodige geschriften…, 1679.

After 1650, the production of copybooks dropped down drastically in the Netherlands. In the last quarter of the century, however, a few masters published a few nice copybooks which were quite different from the ones published before : they offered significantly less examples of gothic script and focused almost solely on “humanistic scripts” (mainly the italian hand as well as its “evolved” forms like the french bastard). Perling’s books excelled in quality : he was the only master from this new generation whose name was mentioned next to those of Velde, Strick and Roelands by 18th century masters like Bickham, Clark and Champion… His work actually had a big influence on these English writing masters who would develop the English Round Hand.

PERLING (Ambrosius), Schat Kamer…, 1685.

This book contains nice examples of the cursive or “running” script that would inspire the British masters a few years later.

PERLING (Ambrosius), Album met schrijfvoobeelden van Ambrosius Perling, c.1685.

From what I understand, the few plates gathered in this Album do not constitute an actual copybook published by Perling himself. However, the quality of the photographs really do justice to Perling’s mastery of the pen.

KOMANS (Michiel), Dienstige voorschriften voor de leergierige in de schrijvkonst, c.1690.

Michiel Komans’ style was similar to Perling and his books focused mainly on humastic hands. The copy from Google is not of great quality, three plates are scanned here.

KOMANS (Michiel), Inleiding tot de Schryvkonst, c.1690.

This small book was specifically made to help students learn how to read and write : only one line per page, with demonstrations of each letter followed by lines to copy as practice.

PERLING (Ambrosius), 10 plates with traits de plume, c.1693.

You won’t find any calligraphic specimen within these pages, only beautifully executed “traits de plume” (offhand flourishes), some of which are really close to those seen in 18th century English copybooks.

France

LE BE (Pierre), Béle prairie, où chacun peut voir les lettres tant romaine que de forme en leur fleur et perfection…, 1601.

Pierre Le Bé came from a typographical background, his father being the successor of Garamond. He chose to work as a “Maître écrivain” and published this little book when he was still young. Even though the title page gives a good idea about his skills as a penman, the book itself is a thorough description and illustration on the best way to draw Roman capitals (Trajans) and gothic lowercases. It also includes a model of cross-stitched alphabet in Trajans.

BEAUGRAND (Jean de), Panchrestographie ou exemples de toutes les sortes d’escritures, 1604.

Jean de Beaugrand taught the art of writing to the future king Henri XIII, the book is dedicated to his illustrious student. His models include some french gothic hand and the “new” italian hand. Unfortunately, the photos linked here are a little blurry, but you can also see this book by following the next link.

BEAUGRAND (Baptiste de), Poecilographie ou diverses écritures propres pour l’usage ordinaire…, 1606.

The brother of the previous Beaugrand… and as talented as his brother. The linked scan also includes the work of Jean de Beaugrand in better quality. The flourishes illustrating both books show the bother’s ingeniosity in inventing new variations, something they were quite proud of.

MATEROT (Lucas), Les œuvres de Lucas Materot…, 1608.

Lucas Materot was a vey talented master penman in the papal chancery in Avignon. This book, beautifully engraved, is essentially dedicated to the italian hands. One very interesting plate had a special influence in the development of calligraphy in the 17th century : beginning with “S’ensuit la lettre batarde” (p.97), shows a simplified version of the italian hand that would serve as the first examples of french Batarde hand and greatly influence the English writing masters who developed the English Round Hand a century later…

PAVIE (Marie), Le Premier essay de la plume de Marie Pavie, 1608.

This is one of the first writing manuals published by a woman (see Maria Strick in the Netherlands). The aesthetic in this book is close to the Beaugrand bothers’ even though the result is not as fluid.

DESMOULINS (François), Le paranimphe de l’escriture ronde, financiere et italienne de nouvelle forme…, 1615.

Desmoulin was a talented calligrapher who was able to write in a very flowing style. His talent for what we now call “offhand” flourishing was phenomenal and has been compared to Schwander’s (1756).

BARBEDOR (Louis), Les Escritures financière et italienne-bastarde dans leur naturel…, 1647.

Barbedor is one of the great masters who lived during the reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV. He was offically assigned the task of writing the “Ronde” exemplars which were to serve as models throughout the kingdom (Pierre Le Bé’s younger brother, Etienne, provided the official models for the Batarde). Barbedor is also credited with having perfected the national script (making it look a little less gothic, simpler in appearance). This book was his major publication, and went through multiple republications ; one, which has a longer introduction, can be seen here. As the French government had decided to trim down the number of scripts practiced in France to only 2 hands, this copybook focuses on the Ronde and the “Batarde Financière” (basically a perfected version of the Ladies hand seen in Materot’s book). Barbedor was opposed to adding the “Coulée” to the French hands because he feared that it would open the door to over-simplification, eventually leading to poorly written or illegible scribbles…

DU MINY (Louis), Les pièces d’escritures de toutes les lettres usitées en ce Royaume et necessaires en toutes sortes de charges…, 1648.

Louis Du Miny’s style is very close to Barbedor’s, he was highly regarded, but only a few of his works can be seen today. This book was engraved and printed posthumously by his son in law (Daubertin) who was also a “Maitre Ecrivain” in Paris. Therefore, the date 1648 may not be accurate…

COYMANS (Eliana), collection of manuscripts, 1661.

Mostly french influenced hands.

SENAULT (Louis), Livre d’écriture représentant naïvement la beauté de tous les caractères financiers..., 1668. (with full preface here)

Senault is regarded as the most illustrious pupil of Barbedor. He was also a very good engraver and always used his left hand to engrave in order to keep his light “touch” with the right hand (which he used to write). He published many copybooks, this one being described as his “chef d’oeuvre”, and also wrote and engraved religious books (you can see one here).

SENAULT (Louis), Curieuses et nouvelles recherches des escritures financieres et italiennes bastardes…, c.1668.

Unfortunately, only a few pages are scanned.

DUVAL (Nicolas), Le Trésor des nouvelles écritures de finances et italiennes bastardes à la mode avec les belles instructions et secret…, 1670.

Duval was also a very talented writing master whose talent rivalled Senault’s. As many others, he engraved his own books and did it well. This is his major publication, which includes a few pages of instructions on how to sit, cut a quill, make ink…

ALAIS DE BEAULIEU (Jean-Baptiste Jr), L’art d’écrire, 1680.

This is a major book in the history of the teaching of writing in France, and it had a enormous success. Following a few letterpressed pages of thorough explanations, the plates give a few models to copy from and clear demonstrations on how to cut a quill, shape the letters from basic strokes and link them together… Alais put the “technicity” of writing (the quality of the touch and the stroke) over the perfection of the form.

MAVELOT (Charles), Nouveau livre de chiffres qui contient en général tous les noms et surnoms entrelassez par alphabet, 1680.

Mavelot was a Maitre Ecrivain as well, but this book is not a usual copybook. Mavelot’s specialty was in designing monograms and in heraldry, this particular volume is dedicated to monograms. I’m listing his other volumes below, regardless of the dates of publication.

Nouveau livre de chiffres par alphabet à simple traits où se trouvent tous les noms et surnoms, c.1684. (Monograms)

Nouveau livre de différents cartouches, couronnes, casques, supports…, 1685. (heraldry : models of crests)

Nouveaux desseins pour la pratique de l’art heraldique de plusieurs armes des premiers de l’Estat..., 1680. (heraldry : crests of important people in France at the time)

BLEGNY (Etienne de), Les Elemens ou premières instructions de la jeunesse, 1691.

This book dedicated to “the first things that are taught to young people” was very successful and went through multiple reprints. Blegny divided it in eight parts going over several subjects taught in schools (writing, orthography, vocabulary, how to write letters, accounting…). The part about writing explains perfectly the principles of the art, it was illustrated with a few really nice plates focusing on the Ronde and the Batarde (these plates can also be seen here in better res). Blegny enjoyed illustrating his plates with off-hand illustrations of animals and angels.

LESGRET (Nicolas), Le livre d’exemplaires composé de toutes sortes de lettres de finance et italienne bastarde, 1694.

Lesgret was a brilliant calligrapher who was selected to teach his art to young princes and people at the court ; this was his first copybook. The structure of this book is similar to other French copybook : a section in letterpress giving instruction on a variety of subjects and a section illustrated by beautiful plates (one plate seems to be missing in this copy). Lesgret was one of few masters to have taken an interest in the anatomy of writing.

England

DAVIES OF HEREFORD (John), The Writing Schoolemaster, or the Anatomie of faire writing..., 1648.

John Davies, from Hereford, who was also a prolific poet, became known as the best penman of his day. This copybook was written and published before his death in 1618, but the only copies that are known today are posthumous republications like this one. Another strange copy only containing the letterpressed pages can be seen here.

BILLINGSLEY (Martin), The Pen’s Excellencie or the secretaries delighte, 1618.

This is one of the first english copybooks containing plates of engraved models, I find the introduction especially interesting as it sheds light on the context in which it was published (see here for more information). The market of copybooks in Great Britain was very different from the continent, the quality of this book was above average, which made it a very popular publication. Billingsley was chiefly noted for his italian hand, but he included in his book “all the usual hands” practiced in England as well.

GETHING (Richard), Calligraphotechnica…, 1619.

Gething was very highly regarded by his fellow writing masters, his work is clearly influenced by Velde’s “Spieghel”, though it is noticeably more austere. John Davies was his teacher.

BILLINGSLEY (Martin), A copy book containing both experimental precepts and usual practices…, 1637.

This copy book focuses a little more on basic forms (and ductus) than Billingsley’s first publication, the model are simpler and more approachable for less experimented penmen. The copy owned by the University of Umea has been extensively used by one of its owners who left his own mark on the pages.

ANON, Directions for writing set for the benefit of poor schollers, 1656.

This is a copybook that was printed from wooden engraved plates, probably using some illustrations that were “lifted” from older copybooks, which made it cheaper. The ductus for english secretary letters is given, it also contains pages of various instructions and models for the Italian hand and court hand.

COCKER (Edward), The pen’s transcendencie…, 1657.

Cocker is often described as one of the greatest penman in 17th century England, he most certainly was the most prolific author of copybooks (17 copybooks are accounted for today). He was just 26 when he wrote and engraved this third publication. All of his books are populated with lavish off-hand flourishes. The fashionable Italian hand occupies a good place in this book, but all the other traditional english hands are not overlooked. Like many of his peers, Cocker also taught arithmetics, and is actually better known for publishing a textbook on the subject, the popularity of which gave rise to the phrase “according to Cocker,” meaning “quite correct.”

COCKER (Edward), Arts glory, or the Penman’s treasury, 1657.

COCKER (Edward), The pen’s triumph, 1658.

HODDER (James), The Pen-mans Recreation : or a Copy-book newly published…, 1659.

A copy book engraved by Cocker. It contains a lot of “spaghetti” flourishes and some fun off-hand creatures as well as the usual hands.

COCKER (Edward), England’s Pen-Man : or Cocker’s New Copy-book, 1671. (added Sept. 2020)

A 1701 reprint from a private collection, kindly scanned and shared by Dr Joe Vitolo.

COCKER (Edward), Magnum in Parvo ; or, the Pens Perfection…, 1672.

Contains an interesting plate explaining the succession of strokes for an intricate ornament.

SNELL (Charles), Penman’s Treasury open’d, 1694.

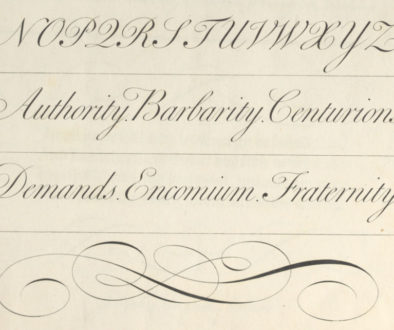

Until then, the English writing masters had focused their copybooks on the traditional British hands, allocating gradually more space to the fashionable “italian hand”. Snell is among the penmen who introduced the french Batarde, as seen in Materot’s and Barbedor’s works, to the English public. Their style, also influenced by some Dutch masters like Velde and Perling, would soon evolve into the first version of the English Round Hand. All of those influences can be seen in this copybook, but Snell was also criticized for being too analytical, making his style overly technical and cold.

HATTON (Edward), The Merchant’s Magazine, 1695.

This book is a manual of arithmetic that was successful enough to go through a number of republications until at least 1734. It contains 9 plates written in the italian hand by the author himself.

SEDDON (John), Penman’s Paradise, 1695.

Little is known about John Seddon’s life, except that he died in 1700. He excelled in the “ornamental” part of writing and adorned the pages of this copybook with lots of examples of “command of hand” (flourishes), that would later appear in other penmen’s works. Below the portait published in this book, we can read “when you behold this face, you look upon the great Materot & Velde all in one” : not only did Seddon look up to these illustrious legends of penmanship, he wanted people to think he had exceeded their talent.

AYRES (John), Tutor to penmanship, 1698.

Ayres was from the generation that came before Snell, this is far from being his first publication, but it is the most important one. Ayres boasted to have been the first to have published the “new” French “a-la-mode secretarie” (the french Batarde) in 1780. His writing style was heavily influenced by Materot and Barbedor, while his flourishes were close to the Dutch aesthetic. The traditional hands used in England and the italian hand still occupy a good amound of space in this publication, but we can already recognize the future English hand in these pages.

Italy

CURIONE (Lodovico), Scelta dell’opere di Lodovico Curione…, c.1600.

Another book by Curione, which contains some detailed examples of the Italian hand.

SEMPRIONIO LANCIONE, La theorica del nuevo modo di scrivere la cancellaresca, 1601.

This is also a book for the Italian hand, with nice close-ups so you can study the details.

PICCHI (Cesare), Libro primo di cancellaresche corsiue, 1609.

SELLARI da CORTONA (Giuliano), Laberinto di varii carateri, 1635. (added October 2020)

A typical example of 17th century italian copybook, with a plethora of border flourishes. It displays beautiful examples of italian hand.

TENSINI (Agostino), La Vera Regola dello Scrivere, c.1680.

Another typical Italian example with a good amount of “striking” or offhand flourishes.

Spain

DIAZ MORANTE (Pedro), Arte de escriuir, 1616.

Pedro Diaz Morante published his major copybook in four parts in 1616, 1624, 1629 and 1631 (click on the dates to go to the available copies). Unlike his Spanish colleagues, he gave very little instructions in his books, suggesting that copying his work would be the best way to learn. In 1776, Palomares published his own copybook in which he included over 70 pages of comments on Diaz Morante’s techniques as well as plates heavily influenced by the master’s works (see it here).

CASANOVA (Jose de), Primera Parte del arte de escrivir..., 1650.

Casanova displays a variety of hands in this book, but the examples that I find most striking are those demonstrating the Italic script (cancellaresca formata). Casanova also dedicated a lot of plates to the Bastarda, with some very pretty lowercase variations.

ORTIZ (Lorenzo), El Maestro de escrivir, 1696.

A manual containing letterpressed instructions for the most part. A few plate illustrate the spanish version of Italic and Italian scripts, as well as roman capitals and lowercases.

Germany

NEUDORFFER (Anton), Schreibkunst, 1601.

Anton Neudörffer was the grandson of Johann Neudörffer, who is known as the father of German calligraphy (and the first to have used metal engraving to reproduce writing). This book is actually a reissue of Johann’s book Gesprechbüchlein (1549), with some additional plates. Only the third part of this copybook was printed from copperplates, it includes a great variety of gothic alphabets. Neudörffer’s book had some influence outside of Germany, Austria and Switzerland, mainly in the Dutch Republic and in England.

Collection of manuscripts from various sources, second part, .

this is a comment